|

Exactly 100 years ago, on March 11, 1918, a U.S. Army private went to the hospital with cold-like symptoms. He was the first patient diagnosed with what became known as the “Great Influenza,” a pandemic that swept the globe and eventually killed tens of millions of people.

Mysteries about that pandemic endure today. Why did it kill mostly the young and able? Why did the flu hit communities in repeated waves? Epidemiological detectives are still digging through old church records, military archives and cemeteries for clues about exactly what happened and when.

Back in 1918, few people had even heard of viruses, never mind connected one to the deadly pandemic. Tufts University disease ecologist Jonathan Runstadler describes how far the science has come, now recognizing how animals around us can be a reservoir for pathogens that might infect people. Learning more about virus strains in the wild could help scientists predict and respond when an infection spills over to humans and makes people sick.

Influenza still hits every year, and the severity of this flu season surprised health experts. Could a future pandemic also wreak worldwide havoc? University of Florida physician and epidemiologist Nicole Iovine explains that vaccination has minimized the risk of a pandemic, but that “we must continue to support research efforts aimed at developing a universal influenza vaccine.”

|

It can be difficult to find records from epidemics long past.

U.S. National Library of Medicine

Gerardo Chowell, Georgia State University; Cecile Viboud, National Institutes of Health; Lone Simonsen, Roskilde University

One hundred years after a strange and devastating pandemic, researchers comb for clues in dusty libraries, church records and long- forgotten books.

|

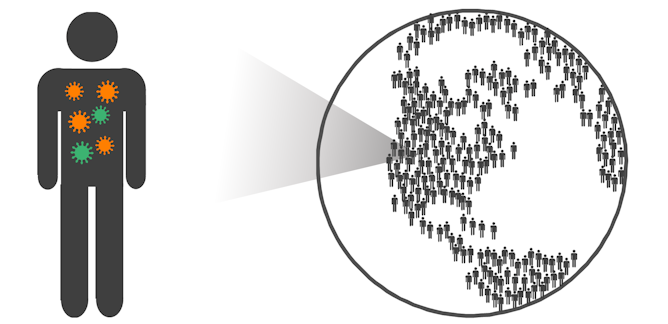

People and animals live side by side – and can have pathogens in common.

Nichola Hill

Jonathan Runstadler, Tufts University

No one then knew a virus caused the 1918 flu pandemic, much less that animals can be a reservoir for human illnesses. Now virus ecology research and surveillance are key for public health efforts.

|

An injectable flu vaccination. Flu vaccines lessen the likelihood of getting the flu and its severity.

Flickr/

Nicole Iovine, University of Florida

The 1918 flu pandemic has long puzzled those who study disease outbreaks. Why was it so severe? While that question is hard to answer, one thing is certain: Vaccines would have lessened the toll.

|

1918 pandemic and the flu today

|

Christine Crudo Blackburn, Texas A&M University ; Gerald W. Parker, Texas A&M University ; Morten Wendelbo, Texas A&M University

With many men 'missing' from the population in the aftermath of the 1918 flu, women stepped into public roles that hadn't previously been open to them.

| |

Richard Gunderman, Indiana University

Don't believe these 10 common myths about the 1918 Spanish flu.

|

Katherine Xue, University of Washington; Jesse Bloom, University of Washington

New genetic technologies are letting us look at flu evolution right where it starts: within individual people, while they're sick.

| |

Laura Haynes, University of Connecticut

Anyone who's had the flu can attest that it makes them feel horrible. But why? What is going on inside the body that brings such pain and malaise? An immunologist explains.

|

Lance Gable, Wayne State University

Science has come a long way in the 100 years since the worst flu pandemic in history. But that doesn't mean that the country is ready for another health disaster.

| |

Ian Setliff, Vanderbilt University; Amyn Murji, Vanderbilt University

Flu virus mutates so quickly that one year's vaccine won't work on the next year's common strains. But rational design – a new way to create vaccines – might pave the way for more lasting solutions.

|

|

|