|

|

|

Editor's note

|

|

Nearly five years have passed since Boko Haram kidnapped more than 200 schoolgirls from Chibok, Nigeria, prompting worldwide outrage and triggering the #BringBackOurGirls campaign. Today, four young women who escaped the infamous kidnapping are studying at a small private college in Pennsylvania. A visiting professor who is helping to prepare the young women for college describes their quest for higher education and their struggle to find

new meaning in life.

The rapid advance of artificial intelligence has prompted alarmists to offer dire warnings about the coming “robot apocalypse.” Even if AI-powered machines don’t enslave us, they’re still expected to steal most of our jobs. Thomas Kochan and Elisabeth Reynolds, scholars on the future of work, explain how society can avoid this kind of apocalyptic outcome.

And inside a prison in Connecticut, older inmates who are serving life sentences are mentoring younger inmates in preparation for their release, writes law professor Miriam Gohara. This pilot program, based on a model used in Germany, offers a new way of thinking about people who commit crimes – as victims with unhealed trauma.

|

Jamaal Abdul-Alim

Education Editor

|

|

|

Top stories

|

Chibok schoolgirls freed from Boko Haram captivity shown in Abuja, Nigeria in 2017.

Olamikan Gbemiga/AP

Jacob Udo-Udo Jacob, Dickinson College

Four young women who escaped Boko Haram during the 2014 Chibok schoolgirl kidnapping are now studying in the US. Their professor recounts a recent breakthrough in their quest to go to college.

|

Some soothsayers predict robots will take over half of today’s occupations.

Mykola Holyutyak/Shutterstock.com

Thomas Kochan, MIT Sloan School of Management; Elisabeth Reynolds, Massachusetts Institute of Technology

While some alarmists predict AI will decimate the workforce, the truth is concerted action by leaders in labor, business, government and education can ensure workers aren't replaced by robots.

|

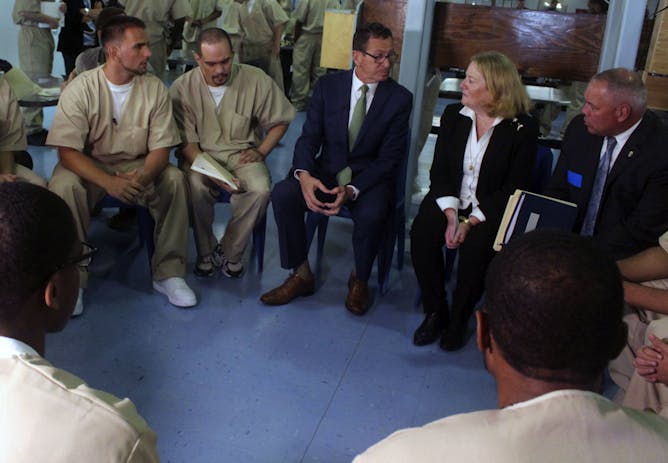

Former Connecticut Gov. Dannel P. Malloy speaks with inmates.

AP Photo/Pat Eaton-Robb

Miriam Gohara, Yale University

In a pilot program, older prisoners sentenced to life mentor younger prisoners who have a chance to lead productive, lawful lives when they get out. The focus is on healing trauma.

|

|

|

Health + Medicine

|

-

Allison Webel, Case Western Reserve University

Headlines around the world declared that a second person was cured of their HIV. But while the results are encouraging, we're a long way from a cure.

-

Deepa Burman, University of Pittsburgh; Hiren Muzumdar, University of Pittsburgh

One of the most dreaded times of the year occurs this weekend, when Americans spring forward - and lose an hour of sleep in so doing. Two doctors who are sleep specialists offer some survival tips.

|

|

|

|

|

|

Science + Technology

|

-

Sarah Scheffler, Boston University; Adam D. Smith, Boston University; Ran Canetti, Boston University

When algorithms are at work, there should be a human safety net to prevent harming people. Artificial intelligence systems can be taught to ask for help.

|

|

Most read on site

|

-

Chitralekha Zutshi, College of William & Mary

India and Pakistan have been fighting for control over Kashmir, an 86,000-square-mile territory in the Himalayas, for seven decades. But the people of Kashmir have their own political goals too.

-

Steve Calandrillo, University of Washington

Washington, California and Florida are mulling a permanent switch to DST. Proponents say that doing so could improve health, save energy and prevent crime.

-

Yana Rodgers, Rutgers University

Abortion rates tripled in Latin America and doubled in Africa under the Bush-era 'global gag rule.' The law, which Obama repealed and Trump reinstated, cuts funding for abortion providers abroad.

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|