The very first educational video our CME group produced — entitled “Hormonal Manipulation for the 1980s” — featured a homemade animation from the nascent University of Miami audiovisual department depicting the mechanism of action of tamoxifen complete with side-by-side Pac-Man-like images of the drug and an estrogen molecule scooting across the cell membrane and racing to the nucleus to bind with a reverse-Pac-Man-looking estrogen receptor.

The very first educational video our CME group produced — entitled “Hormonal Manipulation for the 1980s” — featured a homemade animation from the nascent University of Miami audiovisual department depicting the mechanism of action of tamoxifen complete with side-by-side Pac-Man-like images of the drug and an estrogen molecule scooting across the cell membrane and racing to the nucleus to bind with a reverse-Pac-Man-looking estrogen receptor.

Back then this biology was very cool, and although we welcomed aromatase inhibitors (AIs) and fulvestrant to clinical practice, for a long time thereafter it seemed like there wasn’t much progress beyond this primitive concept of the very first form of targeted treatment of cancer. Instead the new target on the block, HER2, was generating considerably more interest as dashing figures like Dr Dennis Slamon regaled us with impressive science and trial results to match.

It was only in 2011 that research on endocrine treatment began to awaken from its long slumber, when data from the Phase III BOLERO-2 study demonstrated an impressive progression-free survival (PFS) hazard rate (HR) of 0.36 with the addition of the mTOR inhibitor everolimus to exemestane in patients with ER-positive advanced disease. Unfortunately, the toxicity of this agent, particularly mucositis, somewhat dulled our collective enthusiasm.

And then along came the results from a fascinating randomized Phase II trial presented by Dr Richard Finn (a UCLA and BCIRG/TRIO colleague of Dr Slamon) at the 2012 San Antonio Breast Cancer Symposium evaluating a novel small molecule with a strange name (palbociclib [palbo]) and an even weirder target (CDK 4/6). At the conference the tremendous buzz around this story was quickly mixed with a healthy dose of skepticism based on the prior Phase III disappointment (following impressive Phase II data) with the PARP inhibitor iniparib, and many wondered if this might be déjà vu all over again. As a result most investigators were cautious in their ensuing discussions about palbo and quite surprised in February of this year when the FDA boldly approved the drug in combination with letrozole as first-line treatment for metastatic ER-positive, HER2-negative disease.

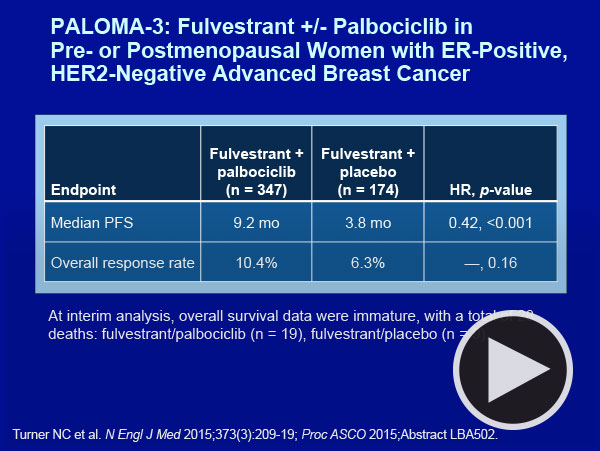

Fast forward to this June at ASCO, when it became clear that the Feds were in fact quite prescient as we were treated to the results of the Phase III PALOMA-3 study — an international effort evaluating fulvestrant with or without palbo in women with ER-positive, HER2-negative metastatic breast cancer (mBC) that progressed on either chemotherapy and/or prior endocrine therapy. The trial reported a clinically and statistically significant improvement in PFS (9.2 months with palbo/fulvestrant versus 3.8 months with fulvestrant alone; HR = 0.42; p <0.000001), and in a heartbeat, endocrine treatment bumped HER2 from its throne and once again grabbed hold of our interest and imagination.

To sort out what this development and others in the management of ER-positive breast cancer mean to daily patient care and clinical research I sat down with Drs Lisa Carey and Eric Winer, and this, the first of 2 programs developed from that conversation, provides an array of video highlights focused on palbo, other CDK inhibitors and the remarkable evolution of genomic assays in the selection of systemic therapy for patients with localized ER-positive, HER2-negative disease. The video comments are available with a quick click and are summarized below.

1. CDK 4/6 inhibitors in metastatic ER-positive disease

| Palbo |

|

With that said, the faculty and most investigators seem pretty convinced of the likely overall positive risk-benefit equation with the addition of palbo to endocrine therapy for patients with mBC. Thus, when asked to describe a situation in mBC in which one would not add palbo to endocrine therapy, Dr Carey — after a long pause — suggested that she might not include the drug for a patient with a long disease-free interval, perhaps off endocrine therapy, with limited tumor bulk. This dramatic shift in practice also affects the use of the previously approved everolimus, which now seems to be clearly positioned post-palbo, but currently the exact clinical indication for this mTOR inhibitor is difficult to ascertain.

The optimal selection of an endocrine partner for palbo is open to debate, but neither faculty member was ready to combine it with tamoxifen. For the important and common situation of a patient with disease relapse on an AI, Drs Carey and Winer found PALOMA-3 convincing enough to feel very comfortable in most cases with this combination.

|

| Other CDK inhibitors: abemaciclib (abema), ribociclib |

|

In spite of the responses observed to single-agent treatment, the major emphasis of ongoing research with abema is in combination with endocrine therapy, which seems to be the optimal route based on what is known clinically and from the laboratory. At ASCO, Dr Winer’s Dana-Farber colleague Dr Sara Tolaney presented results from a Phase Ib trial of 73 patients evaluating abema with a variety of endocrine agents and reported an impressive overall disease control rate of 67% among 36 patients treated with abema/nonsteroidal AI and 75% among 16 patients treated with abema/tamoxifen. Abema and the other major CDK 4/6 inhibitor in later stages of development, ribociclib (LEE011), along with palbo, are the subjects of a plethora of ongoing studies not only in breast cancer but also in other tumors, including non-small cell lung cancer, melanoma and liposarcoma, that harbor the major target of these agents (retinoblastoma tumor suppressor protein).

Dr Carey, who coauthored the New England Journal editorial accompanying the PALOMA-3 publication, hopes that the future use of these agents will be dictated by tissue predictors of benefit, which will reduce the potentially considerable societal and personal financial burden of treatment, and she also related her belief that cytopenias, fatigue and gastrointestinal (GI) toxicity are all class effects that vary in intensity by agent. It could be that all 3 of these compounds may end up available for use and choices will be made based on comparative efficacy and tolerability. Dr Winer notes that these agents have yet to demonstrate an overall survival benefit and therefore “it is not wrong” to be more conservative about utilizing them currently.

| Case presentations

To delve deeper into this issue, we asked the faculty to present cases, and Dr Winer was eager to discuss a 45-year-old woman from his practice who after more than 3 years on adjuvant tamoxifen experienced disease progression with symptomatic bone metastases. In Eric’s estimation this woman was clearly postmenopausal from adjuvant chemotherapy, so he decided to go with palbo (which had been recently approved) in combination with letrozole. The patient responded to treatment but required a dose reduction due to asymptomatic neutropenia. Dr Carey then presented a postmenopausal woman with indolent metastatic disease who received a nonsteroidal AI for more than 5 years but upon clear-cut disease progression entered a trial of exemestane and abema. The patient experienced good disease control, but after life on a steroidal AI alone with minimal side effects she noted fatigue and GI symptoms that required a dose reduction, which resolved the problem. Dr Winer noted that although tolerability issues with CDK inhibitors seem manageable in the metastatic setting, these may be received very differently as adjuvant treatment. |

| 2. Adjuvant/neoadjuvant ER-positive tumor board |

|

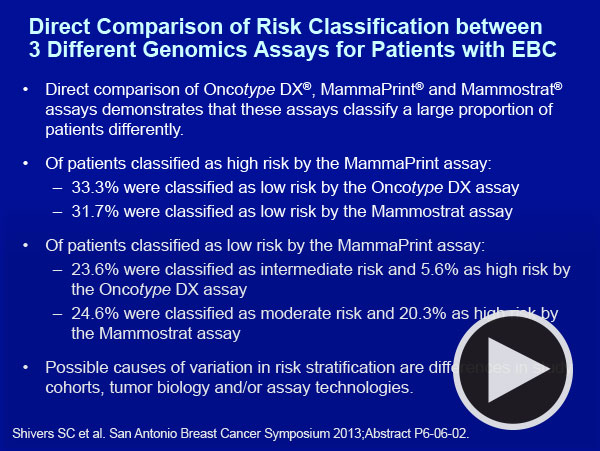

To illustrate where there is consensus and where there is controversy we asked the faculty to present patients from their practices with localized ER-positive, HER2-negative tumors for whom genomic assays were considered.

| Adjuvant chemotherapy in patients with node-positive disease: Anatomy versus biology |

|

In discussing the background of this case Eric commented on the advanced level of numeracy he observes in today’s patients coming to his tertiary center, and he no longer adheres to the traditional belief that many individuals are willing to receive chemotherapy for a 1% to 2% absolute risk reduction, particularly when confronted with the small but similarly sized chance of serious treatment complications — for example, the development of myelodysplastic syndrome/acute myelogenous leukemia.

In terms of how this plays out in clinical practice, both faculty members routinely use the RS in patients with node-negative tumors. However, for node-positive cases like this one Dr Winer gives considerable credence to a SWOG data set demonstrating the predictive value of the RS in postmenopausal patients with node-positive tumors. As such, he routinely uses the assay in patients with limited nodal involvement, generally 1 to 3 positive nodes, the same criterion as the recently completed but not yet reported Phase III RxPONDER trial that randomized patients with a RS of 25 or lower to chemotherapy or not in addition to endocrine therapy.

Furthermore, although the SWOG study was in postmenopausal women, he applies this approach to patients regardless of menopausal status with the thought that “biology trumps anatomy.” Dr Carey, on the other hand, while embracing the biology concept, is not inclined to use the RS or any other assay in patients with node-positive disease. In Dr Winer’s patient the RS was low, which provided the critical impetus to both the patient and physician to forgo chemotherapy, and this woman is now receiving an AI.

|

| Genomic assays to reinforce the need for chemotherapy |

|

| Genomic markers in the neoadjuvant setting |

|

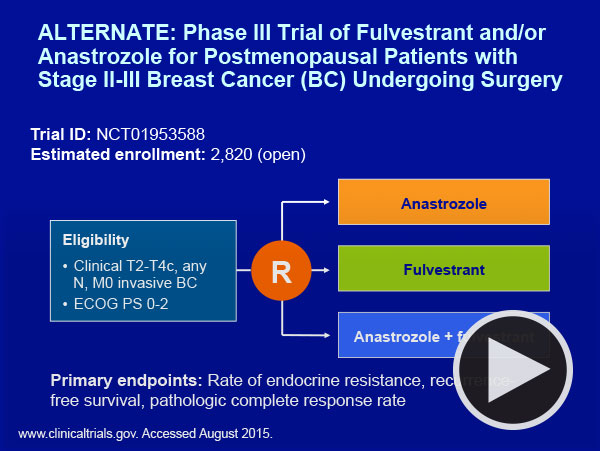

Interestingly, neither faculty member would use a genomic assay in this situation, a practice that our CME group has demonstrated is embraced by more than a third of CIs in cases like this one. Dr Winer also noted that relatively little is known about neoadjuvant endocrine treatment for premenopausal patients, but ongoing trials such as the ALTERNATE study will shed more light on this approach and a current NCI trial led by Dr Harry Bear is evaluating the predictive value of the RS in neoadjuvant treatment in postmenopausal patients. It seems logical that if “biology trumps anatomy” our future choices related to neoadjuvant treatment may end up following similar algorithms as those used postoperatively for essentially the same tumors.

Next, in Part 2 of our conversation with Drs Carey and Winer we look at the always intriguing management of HER2-positive disease and also talk about some new and exciting developments (finally) in the triple-negative setting, including antiandrogens, PARP inhibitors and, yes, anti-PD-1 antibodies.

Neil Love, MD

Research To Practice

Miami, Florida