|

The word “populist” gets bandied around a lot these days, to the extent that it has become shorthand for a certain type of politician, often with specific views on immigration, race and identity. Aurelien Mondon and Alex Yates want us to think far more carefully about what we mean when we use this word. Have we slipped into the habit of saying “populist” when what we really mean is “extremist”? They think so – and argue that there are four very real consequences of conflating the two, all of which amount to lending legitimacy to people who don’t necessarily deserve it.

Mondon is one of two Conversation authors who will be taking your questions on far-right politics at a special event next week. Join us in central London at 6pm on March 6 for an open discussion on what threat the far right poses to democracies in this bumper election year – and what we need to know to take action against it. Register for your place at this free public session here. Rest assured, there will be food and drinks. And feel free to drop me a line directly if you have any

questions about the event.

It’s been about 25 million years since our ancestors lost their tails, providing them with an evolutionary advantage. But a new paper shows us that we fallible humans are still paying the price for that loss.

Happy February 29, by the way. Most of us have a good understanding as to why we have an extra day in a leap year such as this. But did you know why it gets tacked onto the end of February rather than, say January, or any other month?

|

|

Laura Hood

Senior Politics Editor, Assistant Editor

|

|

microstock3D/Shutterstock

Aurelien Mondon, University of Bath; Alex Yates, University of Bath

Extremists benefit when we use euphemisms that confer on them an air of legitimacy.

|

Unlike humans, many animals still have tails.

vblinov/Shutterstock

Laurence D. Hurst, University of Bath

Many evolutionary changes also come with costs.

|

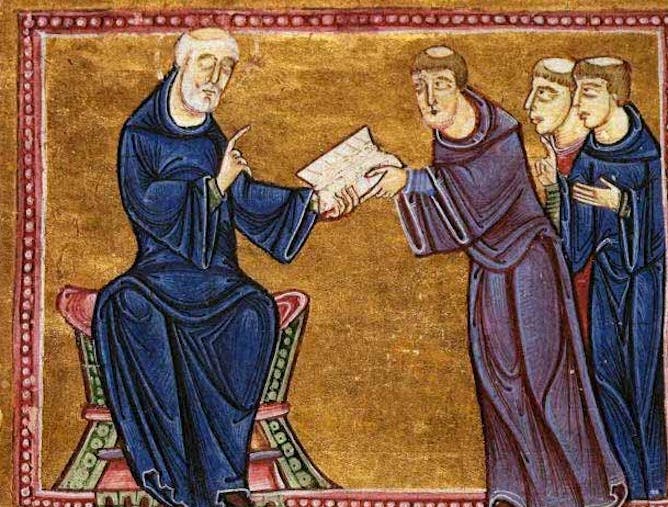

St Benedict delivering his rule to the monks of his order.

WikiCommons

Rebecca Stephenson, University College Dublin

Monks who failed to factor in the leap day placed spring equinox on the wrong day, which meant Ash Wednesday, Lent, Holy Week and Pentecost were also marked on the wrong day.

|

Politics + Society

|

-

Olumba E. Ezenwa, Royal Holloway University of London; Olayinka Ajala, Leeds Beckett University

Ecowas has a patchy track record when it comes to ensuring cooperation and security across west Africa – member states are now starting to leave.

-

Elizabeth Pearson, Royal Holloway University of London

Islamic State has fallen out of the public attention in the UK and Europe but remains active in Africa.

-

Rebecca Haboucha, SOAS, University of London

By targeting a restaurant owner who identifies with a specific cuisine, the protester makes that one person responsible for the actions of an entire group or country.

|

|

Arts + Culture

|

-

David Ekserdjian, University of Leicester

Has Jeff Koons’ latest high-profile stunt just proved that space is the new frontier for art?

-

Timothy Stott, Trinity College Dublin

Jane Harris eschewed the fashionable 1990s London art scene and retreated to rural France where she experimented quietly with shape and colour.

|

|

Business + Economy

|

-

Chris Parry, Cardiff Metropolitan University

Increasing life expectancy and falling birthrates means many of us may have to keep working until beyond 71 years of age.

|

|

Education

|

-

Colin Foster, Loughborough University

Principles from cognitive science can help help in the design of more effective teaching materials for maths.

|

|

Environment

|

-

Morgiane Noel, Trinity College Dublin

As new climate-related cases are brought to court, our expert outlines key aspects that could change the legal landscape.

|

|

Health

|

-

Lisa Graham-Wisener, Queen's University Belfast; Tracey McConnell, Queen's University Belfast

Research suggests that music therapy can help support people before and after a loved one’s death.

-

Sarah Chellappa, University of Southampton

Depression, bipolar disorder and anxiety have all been linked to problems with sleep and a disrupted circadian rhythm.

-

Duane Mellor, Aston University

The Food Standards Agency advises that children under four should not be given these drinks.

|

|

|

|

-

Sarah O'Meara, The Conversation

As a partner on the International Public Policy Observatory, The Conversation is making an impact.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|