|

|

|

|

There’s something simple and satisfying about end-of-season awards in professional sports, such as most valuable player and rookie of the year: There are reams of statistics to evaluate performances, and all of the candidates are more or less on an even playing field.

Movies are trickier − far more subjective, with views on the same performances and direction veering wildly from one critic to the next. For that reason, in the months leading up to the Oscars, there’s a lot of behind-the-scenes politicking, as studios and producers make the case for why their writers, directors, cinematographers, costume designers and actors should win the top prize in cinema.

When Holy Cross theater professor Scott Malia pitched me an article about how Method acting has become widely misunderstood, it served as a reminder that sometimes it isn’t the best performance that wins an Oscar – it’s the best story about a performance. Malia writes about Bradley Cooper’s and Cillian Murphy’s whirlwind media tours to promote their quests to embody their characters, Leonard Bernstein and J. Robert Oppenheimer, respectively.

Will their efforts ultimately influence voters? Or, as The New Yorker wondered of Cooper, “Can you really want an Oscar too much?”

Of course, the Academy Awards are about a lot more than who wins what. They’re a celebration of artists who have mastered their craft, an occasion to look back at iconic moments in film history, a fashion show − and, yes, a chance to witness a viral

slap.

So grab your popcorn and dive into our coverage of Hollywood’s biggest night of the year, from non-English language cinema’s long road to acceptance at the academy to a retrospective of John Williams’ career as arguably the greatest

film composer of all time.

|

|

Nick Lehr

Arts + Culture Editor

|

|

Bradley Cooper as Leonard Bernstein and Carey Mulligan as Bernstein’s wife, Felicia Montealegre, in ‘Maestro.’

Jason McDonald/Netflix

Scott Malia, College of the Holy Cross

Hopefully, Academy Award winners will be chosen because voters believed in the actors’ performances − not because of some meta narrative about their off-screen behavior.

|

Seeing the light − at the movies.

igoriss/iStock via Getty Images

David W. Stowe, Michigan State University

Plenty of movies have explicitly religious themes, but some of the most interesting examples of faith or transcendence on screen are much more subtle.

|

The dress actress Lupita Nyong'o wore to the 86th Academy Awards in 2014 became a story in and of itself.

Jeffrey Mayer/WireImage via Getty Images

Elizabeth Castaldo Lundén, University of Southern California

Through their media savvy, two consultants were able to make the Oscars as much about the attire as the gold statuettes.

|

|

|

Anthony Smith, University of Dayton

Though only a few of Scorsese’s films focus on religious stories, deeper questions about faith, doubt and living in a violent world tend to haunt his movies.

| |

Kerry Hegarty, Miami University

Non-English language cinema – previously seen by niche audiences – is increasingly finding acceptance and recognition, reflecting the many demographic changes taking place within the academy.

|

Naoko Wake, Michigan State University

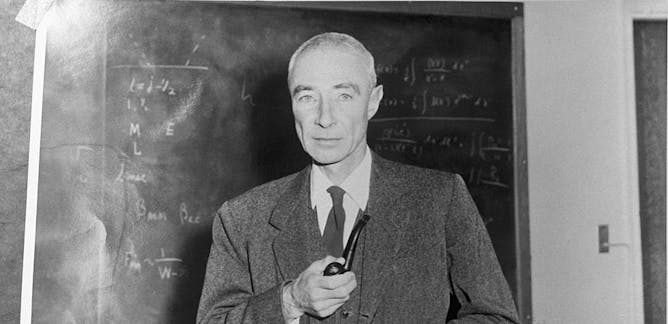

For all its praise, the film furthers the dominant narrative of the bombs as a morally fraught but necessary project, with American anxieties playing a starring role.

| |

Charles Thorpe, University of California, San Diego

Complex as they are, Oppenheimer’s life and views of the bomb are far easier to wrestle with than the reality of nuclear power itself.

|

|

|

|

|

-

Arthur Gottschalk, Rice University

Composer and conductor John Williams has shown for more than 60 years how music can take movies to new heights.

-

Julia Cain, University of Cape Town

An emotional roller coaster, the film tracks the pop star’s political battle up close and personal.

-

Florence Martin, Goucher College

The first Arab woman nominated for two Oscars, Kaouther Ben Hania is a visionary and a feminist.

-

Shannon Toll, University of Dayton

Despite the perpetrators being tried and convicted, anti-Indigenous sentiment roiled the area for decades.

-

Aviva Dove-Viebahn, Arizona State University

Being a mom can be heartbreaking, empowering, scary, fulfilling and everything in between.

|

|

|

|---|

-

More of The ConversationLike this newsletter? You might be interested in our weekly and biweekly emails: Follow us on social media: -

About The ConversationWe're a nonprofit news organization dedicated to helping academic experts share ideas with the public. We can give away our articles thanks to the help of

foundations, universities and readers like you. |

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|