|

I was 20 years old when I got my first paying job in journalism. The Canadian Press hired me as a summer intern fresh out of Ryerson's journalism school and 10 days after I started, I got to work on a federal election. I was one of three interns who stood beside a senior editor overseeing the results that were arriving via teletype from CP correspondents spread across the country. Here’s what I did that night: every time the Conservatives were leading or elected in a riding, I put a blue push pin in a cork board beside the corresponding riding. Another intern was responsible for the red Liberal pins. A third had to handle green (NDP) and black (the Québec-based Social Credit party) pins. The pins served as an updated tally board for the reporters writing the running election stories. It was the 1970s version of CNN’s “magic wall” – minus the indefatigable John King.

Jump ahead a couple of decades and I was the person at CP responsible for “calling” all federal and provincial elections, as well as the 1995 Québec referendum. It’s a nerve-wracking job: no one remembers if you made the right call, but no forgets if you made the wrong call (which I did once during a very close Saskatchewan vote). So, I have plenty of sympathy for those at the Associated Press and the

major U.S. networks that haven’t yet made a call more than three days after the presidential election.

The unpredictably close vote has meant many of us have been glued to some version of an election results map – either on your phone or on TV. Geographer Eric Nost of Guelph University has spent the week analyzing the maps used by different media outlets in Canada and U.S. and notes that not all maps are created equal. It’s a fascinating read at the end of a fascinating week.

Also for your reading pleasure: a collection of some of the latest takes on the presidential election from the global network of The Conversation. And for those who have had enough of presidential politics and are looking ahead to next week, I’ve included a really interesting story about Remembrance Day.

Have a great weekend and we’ll back in your Inbox on Monday.

|

And the winner is...

|

Eric Nost, University of Guelph

What did this year's election maps rightly or wrongly tell us?

| |

Donald Brand, College of the Holy Cross

Judges are generally reluctant to decide elections, as the Supreme Court controversially did in 2020. As a result, Trump's flurry of litigation could wind up throwing the election to the House.

|

Chris Lamb, IUPUI

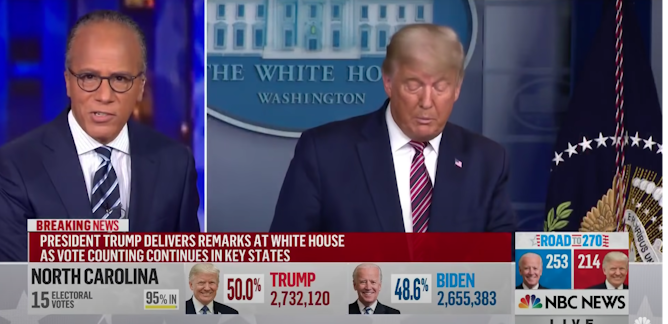

When President Trump claimed in a press conference that the election was being stolen from him, three major TV networks cut off their coverage. A media scholar asks if this is a turning point.

| |

Denis Muller, University of Melbourne

As the US president made unsubstantiated claims about the vote count, many of the major TV networks cut him off. Is this what's best for democracy?

|

Kristin Kanthak, University of Pittsburgh

As vote counts tick upward, people may have questions about why one candidate does better with mail-in votes or in-person ballots. Here are the answers, and an explanation of how the counting happens.

| |

Todd Landman, University of Nottingham

A profile of Joe Biden's home state, which is crucial to securing victory in the 2020 US election.

|

Kate Starbird, University of Washington; Jevin West, University of Washington; Renee DiResta, Stanford University

Election misinformation typically involves false narratives of fraud that include out-of-context or otherwise misleading images and faulty statistics as purported evidence.

| |

Mark Libin, University of Manitoba

British poet Wilfred Owen told readers there is no peace for the dying soldier until we fight against the lie that it is sweet and proper to die for one's country.

|

|

|