|

Debates about compensating Black Americans for slavery began after the Civil War, with unfulfilled promises of “40 acres and a mule.” A century and a half later, some modern critics of reparations dismiss slavery as too long ago to merit recompense. Yet many products of enslaved people continue to play a role in the U.S. economy today.

“American cities from Atlanta to New York City still use buildings, roads, ports and rail lines built by enslaved people,” write Penn State geographer Joshua Inwood and University of California, Berkeley urban planner Anna Livia Brand. Their work documenting this infrastructure demonstrates how slavery continues to generate wealth today.

This week we also liked articles about the young poet Amanda Gorman, amateur and volunteer scientists and white allies in the workplace.

|

The Port of Savannah used to export cotton picked by enslaved laborers and brought from Alabama to Georgia on slave-built railways. Cotton is still a top product processed through this port.

Joe Sohm/Visions of America/Universal Images Group via Getty Images

Joshua F.J. Inwood, Penn State; Anna Livia Brand, University of California, Berkeley

Geographers are documenting slave-built infrastructure, from railroads to ports, in use today. Such work could influence the reparations debate by showing how slavery still props up the US economy.

|

A volunteer looks for waterbirds at Point Reyes National Seashore in California during the National Audubon Society’s annual Christmas Bird Count.

Kerry W/Flickr

Theresa Crimmins, University of Arizona; Erin Posthumus, University of Arizona; Kathleen Prudic, University of Arizona

COVID-19 kept many scientists from doing field research in 2020, which means that important records will have data gaps. But volunteers are helping to plug some of those holes.

|

American poet Amanda Gorman reads a poem during the 59th presidential inauguration at the U.S. Capitol on Jan. 20, 2021.

Patrick Semansky/POOL/AFP via Getty Images

Kathleen M. Alley, Mississippi State University; Mukoma Wa Ngugi, Cornell University; Wendy R. Williams, Arizona State University

The rise in the popularity of Amanda Gorman, the nation's first National Youth Poet Laureate, represents a prime opportunity for educators to use spoken word poetry in the classroom.

|

|

|

-

Jennifer R. Joe, University of Delaware; Wendy K. Smith, University of Delaware

Some people wonder what they can do to support Black colleagues and junior employees who face institutional discrimination at work and elsewhere.

|

|

|

|

-

Deborah Whitehead, University of Colorado Boulder

Joe Biden used the National Prayer Breakfast to call for unity amid 'dark, dark times.' The event has been attended by every president since Dwight Eisenhower in 1953.

|

|

|

|

-

Bevil R. Conway, National Institutes of Health; Danny Garside, National Institutes of Health

Neuroscientists tackling the age-old question of whether perceptions of color hold from one person to the next are coming up with some interesting answers.

|

|

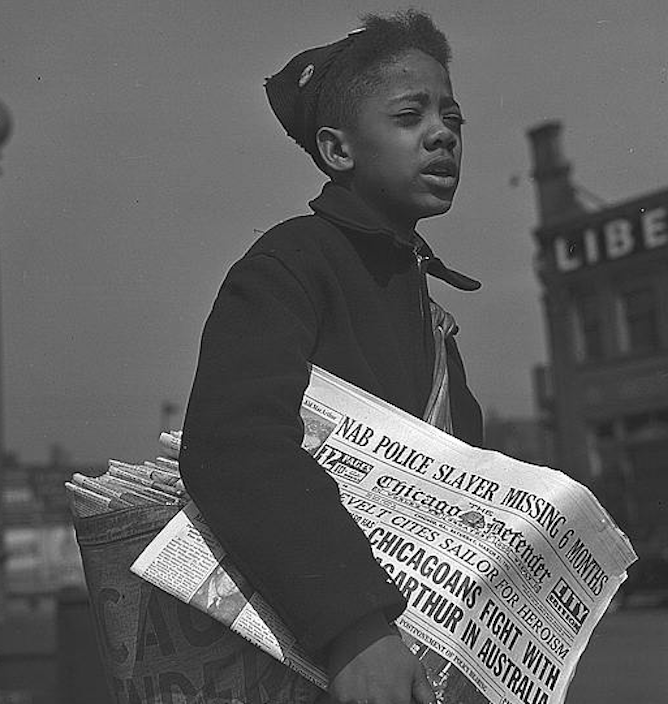

A newspaper boy hawks copies of the Chicago Defender.

Library of Congress

Paige Gray, Savannah College of Art and Design

At the turn of the 20th century, with few children's books featuring Black characters, one young editor implored his peers to 'Let us make the world know that we are living.'

|