|

|

|

|

People have worried about the end of the world for millennia, but it was only in 1945, when nuclear weapons were invented, that we began to think humans ourselves might be responsible for the apocalypse. The scientists who created the atomic bomb were urgently concerned with the possibility of nuclear armageddon, and when they started a magazine in 1947 – the Bulletin of the Atomic Scientists – the cover showed a clock with its hands at seven minutes to midnight.

The hands of the Doomsday Clock, as it became known, are now adjusted each year to represent our current proximity to global catastrophe. While the threat of nuclear conflict receded somewhat with the end of the Cold War, other Earth-sized dangers have appeared on the scene.

This week the Bulletin released its latest assessment: we are at 90 seconds to midnight, as close to doom as we have ever been. According to Rumtin Sepasspour, who studies global catastrophic risks and what we can do about them, there are four main drivers of our planetary peril: the now-familiar prospect of nuclear armageddon, the slower but more certain threats of climate change, the growing danger of pandemics and biological weapons, and the dramatic disruptions

brought by the rapid progress of artificial intelligence.

Critics say the clock’s attempt to quantify the risk of doom is subjective, and sometimes makes little sense. How can you measure the Cuban Missile Crisis and the chance of killer super-COVID on the same scale?

The critics make some good points, Sepasspour writes, but they are perhaps asking a lot of an annual attention-raising exercise: “The Doomsday Clock is not a risk assessment. It’s a metaphor. It’s a symbol. It is, for lack of a better term, a vibe.”

|

|

Michael Lucy

Science Editor

|

|

Rumtin Sepasspour, Australian National University

The Doomsday Clock is not a precise risk assessment, it’s a flawed but powerful metaphor for the catastrophic risk humanity faces

|

Weekend long reads

|

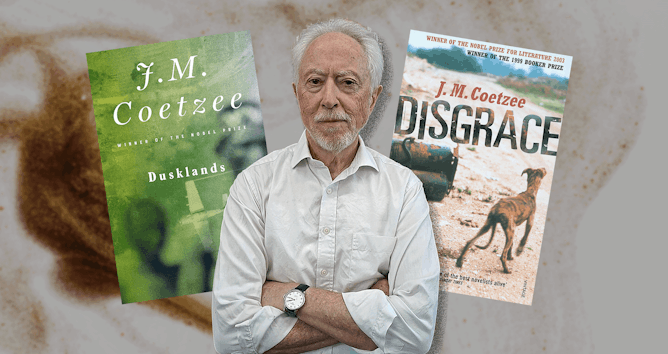

Andrew van der Vlies, University of Adelaide

The fiction of J.M. Coetzee is always formally daring, brave in its social critique and its refusal to play by the rules.

|

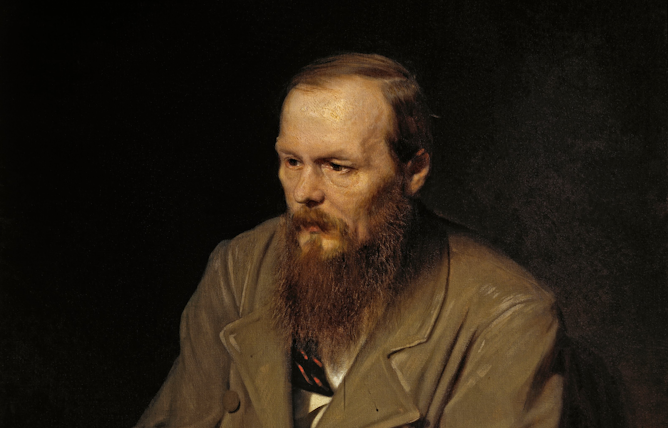

Stephen Dobson, CQUniversity Australia

Dostoevsky’s sudden recovery from his gambling mania is an example of how a chance happening can change everything

|

Sarah Gador-Whyte, Australian Catholic University

A formidable woman born in the second half of the fourth century and widowed at around 17, Olympias was not afraid to advocate for herself – or her friends.

|

Martine Kropkowski, The University of Queensland

Monsters reveal how societies define and punish deviance. Wintering’s widows make me think about the women I know who are strong and wise in ways neither recognised nor endorsed by the mainstream.

|

Chris Mackie, La Trobe University

Reading Wilson’s Iliad, one senses something of the chant of Homer’s verse, even through the written word.

|

Melissa A. Wheeler, RMIT University; Naomi Baes, The University of Melbourne; Samuel Wilson, Swinburne University of Technology; Vlad Demsar, Swinburne University of Technology

Finding common ground is a crucial first step in overcoming differences of opinion and perspective.

|

Our most-read article this week

|

Peter Martin, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

The official figures tell us inflation is 5.4%. But for working families, it’s actually 9%. Yet there is some good news ahead.

|

In case you missed this week's big stories

|

-

David Lowe, Deakin University; Andrew Singleton, Deakin University; Joanna Cruickshank, Deakin University

New polling shows a significant drop in support for January 26 in just two years.

-

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

In the government’s dramatic recalibration of stage 3 all taxpayers will get a cut, rather than just those earning more than $45,000.

-

Steven Hamilton, Crawford School of Public Policy, Australian National University

High earners aren’t particularly highly taxed by historical standards, and the earlier stage didn’t do much for low earners.

-

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

All prime ministers break promises. But there are some whose breaches go into the history books – and Anthony Albanese has just joined that group.

-

Michelle Grattan, University of Canberra

Labor’s new tax package has turned the March 2 Dunkley byelection into a referendum on tax which may leave Peter Dutton with some difficult problems.

-

Frank Bongiorno, Australian National University

Scott Morrison deserves credit for his government’s handling of the economics of the COVID pandemic. But aside from that, he treated politics purely as a game.

-

Denis Muller, The University of Melbourne

At a vulnerable time for the public broadcaster, Williams has made a promising start by saying management must take staff concerns seriously.

-

Denis Muller, The University of Melbourne

The broadcaster’s sacking over a social media post suggests a state of mind induced by two decades of cumulative intimidation, hostility, board-stacking and financial punishment.

-

Peter Greste, Macquarie University

New statistics show a spike in the amount of journalists jailed in the country. To protect its democracy, Israel needs to be transparent about why members of the media are arrested.

-

Ben Rich, Curtin University

The US and UK strikes on the Houthis will have limited impact on the group’s Red Sea attacks – and could cause Middle East tensions to spiral out of control.

-

Nicholas Saner, Victoria University; Olivia Knowles, Deakin University

Night matches at the Australian Open are a great spectacle, but sleep disruption is likely to wreak havoc even on professional athletes.

-

Wesley Morgan, Griffith University

Without urgent action, Earth is heading for climate catastrophe. Yet there are reasons for hope in 2024 – including a possible peak in global greenhouse gas emissions.

-

Tim Flannery, The University of Melbourne

To fight global warming we will soon have to try to remove carbon dioxide from the skies or find ways to reflect the Sun’s heat. Such radical paths must be examined, but risky experiments avoided.

-

Wayne Hall, The University of Queensland

If the scheme isn’t successful, some people may continue using illicit vapes, or to switch to traditional cigarettes.

-

Christian Jakob, Monash University

We crave certainty in our weather forecasts. But that’s only possible for big weather events such as cyclones and major storms. Everything else is probability.

-

Jonathan Nott, James Cook University

The new threat from cyclones can come from behind you – flooding from more intense rainfall.

|

|

| |

|

|

|

Edith Cowan University | Navitas Pty Ltd

Sri Lanka

•

Full Time

|

|

|

University of Tasmania

Hobart TAS, Australia

•

Full Time

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

|

| |

| |

| |

Featured Events, Courses & Podcasts

|

View all

|

|

1 January 2023 - 7 October 2026

•

|

|

1 February 2023 - 25 November 2029

•

|

|

|

|

|

4 March - 13 May 2024

•

Clayton

|

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|