|

Come January, divided government, and all it entails, will set the tone for the 118th Congress. To some, the fact that one party will control the House of Representatives while another controls the Senate means nothing legislatively will get done, at least for the next two years. After all, we can all point to periods when ideological differences and interparty fighting spawned gridlock on Capitol Hill.

But Matt Harris, a political scientist who studies partisanship, writes that legislative results in the next Congress are likely to be about the same as those in a unified government. And there are multiple reasons for that.

“The first reason that divided government isn’t less productive than unified government is that unified government isn’t very productive in the first place. It’s really hard to get things done even when the same party controls both chambers and the presidency,” Harris writes.

He also breaks down the ways divided government could provide real opportunities for Congress to pass legislation and points to significant laws, such as the 2020 Coronavirus Aid, Relief and Economic Security (CARES) Act, that were passed when control of the two chambers was split.

Also in this week’s politics news:

|

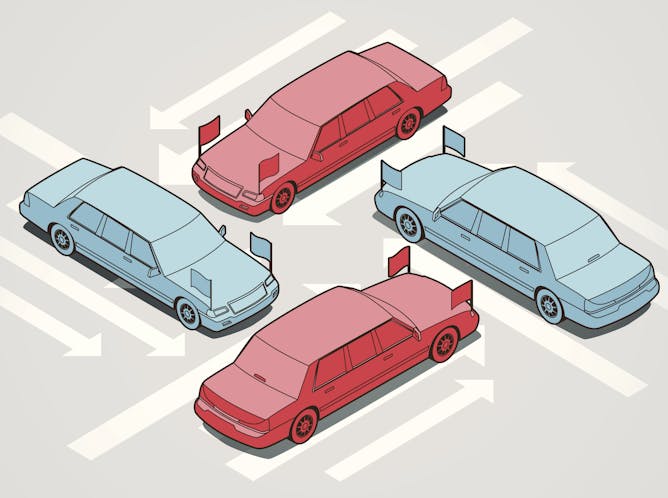

Will gridlock mean the new Congress won’t get anything done?

mathisworks/Getty Images

Matt Harris, Park University

With Democrats running the Senate and the GOP in control of the House, there’s concern that Congress won’t get anything done. Turns out, unified government isn’t very productive in the first place.

|

Hundreds of asylum-seekers gather on the banks of the Rio Grande to enter the U.S. on Dec. 12, 2022.

Jose Zamora/Anadolu Agency via Getty Images

Ernesto Castañeda, American University

Title 42 has triggered criticisms from immigration advocates and public health experts. But some still want to keep it in place and delay accepting asylum-seekers.

|

Reps. Diana DeGette, D-Colo., center, and Veronica Escobar, D-Texas, right, take cover as protesters disrupt the joint session of Congress to certify the Electoral College vote on Jan. 6, 2021.

Tom Williams/CQ-Roll Call, Inc via Getty Images

Derek T. Muller, University of Iowa

Weaknesses in the law governing how elections are run and votes counted in Congress contributed to the Jan. 6 insurrection. An election law scholar analyzes Senate legislation to fix those problems.

|

|

|

Sara J. Brenneis, Amherst College

Spain has long avoided addressing the fact that tens of thousands of Spaniards were victims of Nazis, who collaborated with Spain’s former dictator, Francisco Franco.

| |

William E. Butler, Penn State

When it comes to prisoner swaps it matters if an individual is guilty of committing the crime or whether there has been a miscarriage of justice. And this is where the Griner case gets tricky.

|

Abby Kiesa, Tufts University

About 27% of 18- to 29-year-olds voted in the midterms, marking the second-highest voter turnout in midterms in 30 years.

| |

Joshua Holzer, Westminster College

Special counsels are not entirely independent, but they do still help administrations avoid the perception of bias.

|

|

|

|

|

-

Howard Manly, The Conversation

Sen. Raphael Warnock’s win over GOP challenger Herschel Walker had implications beyond Georgia – and offers a lesson in how far the state has come from its racist past.

-

Theodore J. Kury, University of Florida

The US government regulates many industries, but social media companies don’t neatly fit existing regulatory templates. Systems that deliver energy may be the closest analog.

-

Whitney Shylee May, The University of Texas at Austin College of Liberal Arts

The app best known for kids sharing video clips of themselves singing and dancing has become a powerful tool for activists speaking out against repression in Iran.

|

|