|

|

|

|

On a recent Saturday afternoon, in a 12th-century village church only as wide as a sitting room, I watched my godson and his brothers and their father take off their suit jackets and place them, folded, on the flagstone floor in the corner. Tucking their ties between the buttons on their dress shirts, they stood at the back, near the entrance, and pulled on hemp ropes to ring the church bells for their grandmother. We were celebrating her life as she’d lived it, together, in music.

Music historian Katherine Butler – a campanologist – writes that come next weekend, bellringers in the nation’s 38,000 churches will stand in similar groupings. They will pull on similarly old ropes with tufted woollen sallies, colourfully striped on the diagonal, like boiled sweets. And they will count out similar patterns, or methods, to herald the country’s new king. Ringing the changes is a tradition so steadfast in these parts, Handel is credited with saying

once, of Britain, that it was a “ringing isle”. You don’t need to be ecclesiastically minded to join in. Just Google “local handbell group”.

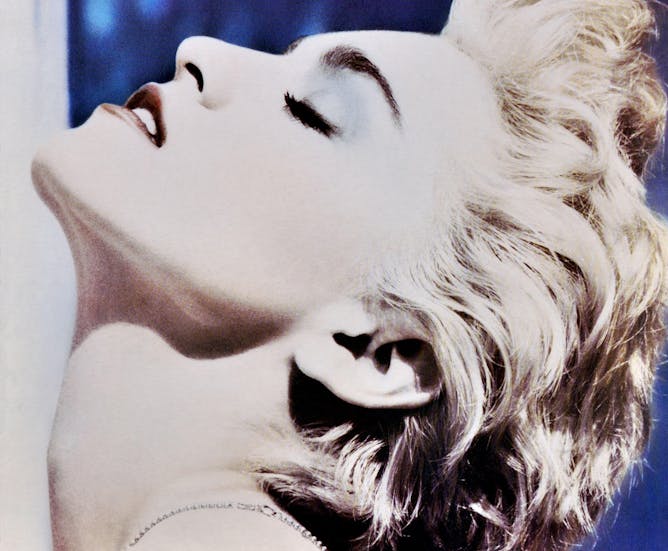

Striking an altogether more disquieting note, a medieval literature expert links Madonna’s recent forays into cosmetic surgery to monastic disfiguration in the 15th century. An environmental chemist, meanwhile, probes pollutants both in the ocean’s deepest depths. Our potential for beauty and destruction both, writ large in bell and face and sediment.

|

|

Dale Berning Sawa

Commissioning Editor, Cities + Society

|

|

Trinity Mirror/Mirrorpix/Alamy

Katherine Butler, Northumbria University, Newcastle

The coronation of Charles III is an opportunity for people to continue Britain’s longstanding campanological tradition.

|

dc photo / Alamy

Laura Kalas, Swansea University

Standards of beauty have been embedded in different cultures, in varying forms, from time immemorial. What endures is that women are still regarded as inferior to men.

|

Scientists found PCBs 8 kilometres below the waves.

dimitris_k / shutterstock

Anna Sobek, Stockholm University

No place on Earth is free from pollution.

|

Politics + Society

|

-

Gordon McKelvie, University of Winchester; Katherine Weikert, University of Winchester

The return of the Stone of Scone to Westminster has proven controversial.

-

Stefan Wolff, University of Birmingham; Tetyana Malyarenko, National University Odesa Law Academy

China’s approach to ending the Ukraine war will determine the future of the European security order.

-

Alessia Tranchese, University of Portsmouth

In focussing on individual “deviancy”, we fail to make the connection between misogyny and wider social problems, like pornography.

-

Sean Dodson, Leeds Beckett University

Digital only commercial news websites still struggle for revenue streams.

-

Naomi Ruth Pendle, University of Bath

Evacuations offer some hope, but only for those that qualify for them.

-

Christoph Bluth, University of Bradford

The US and South Korea are significantly beefing up security arrangements in the face of the perceived growing threat from China and North Korea.

-

Peter John McLoughlin, Queen's University Belfast

Sinn Féin refuses to sit in the Westminster parliament because that would mean recognising the British crown. Here’s why the coronation is a different matter.

|

|

Arts + Culture

|

-

Tionne Alliyah Parris, University of Hertfordshire

Known as the ‘King of Calypso’, Belafonte used his platform as an artist to elevate and support political activism.

|

|

Business + Economy

|

-

Simon Chadwick, SKEMA Business School; Paul Widdop, Manchester Metropolitan University

It’s not just Premier League clubs that enjoy the benefits of being in the spotlight.

-

Shireen Kanji, Brunel University London

Expecting workers to commit to long hours undermines gender equality in the workplace and the home.

|

|

Environment

|

-

Constanza Toro Valdivieso, University of Cambridge

The mystery surrounding a forgotten marine mammal, a remote archipelago and man-made pollution.

-

Ramit Debnath, University of Cambridge; Ronita Bardhan, University of Cambridge

Spring 2022’s record heat put most Indians at greater risk of a premature death.

|

|

|

|

| |

|

|

|

|

| |

| |

| |

| |

| |

|

|

|

|

|

|

|